Thanks to the Black Country Bugle for permission to use this article

Walsall man in service at the home of Lord Tredegar

By Black Country Bugle User | Posted: July 03, 2008

At the end of Queen Victorian’s reign, at the time of her death in 1901, it was recorded that there were 1.7 million women and 140,000 men still employed in domestic service. The great Victorian Age had given the upper and middle class levels of society a considerable amount of wealth, and the tradition of maintaining a house full of servants continued throughout the nineteenth century, and didn’t fall out of favour until after the First World War.

Almost every family history investigation reveals ancestors who were domestic servants at some stage in their lives, and in 1914 domestic service was still the largest single occupation for women. Houses of various sizes would employ as many servants as required to meet the needs and demands of the head of the household; the bigger the house the more servants there would have to be. It had always been the policy to employ new servants from locations at least 30 miles away, for it was feared by those who had the most to lose that younger servants especially might go running home at the first opportunity and spread unwanted gossip. To this end prospective employers advertised the positions available, rather than pass on any vacancies by word of mouth.

Prior to 1891 Frederick Tippett, a working class mon from Walsall, who may well have already been an experienced domestic servant, was hired to work at Tredegar House in Newport, South Wales, the home of Godfrey Morgan Lord Tredegar, a peer of the realm. He had joined a domestic army of 24 which included 15 women and nine men, living and working in the House. Eliza Cook was the housekeeper, a battle-axe of a woman in her sixties, who originally came from Swindon, Wiltshire. She had worked for the Morgans for years, and like so many domestics of her ilk had dedicated her life in service to others and was never married.

Eliza Cook may well have been the person who agreed to take Frederick on, as hiring and firing was one of her main duties. She was also a shrewd woman and didn’t necessarily employ girls who were too young or had no experience of domestic service at all.

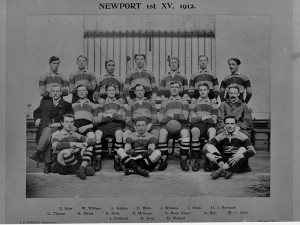

In 1891 the youngest girls living and working at Tredegar House were Elizabeth Hillier aged 20 from Cardiff, and Mary Williams, also 20 from St David’s, Breconshire. The youngest male servant was Frank Sloman from Dorset, who was 19 years old.

Frederick Tippett was single [aged 30 in 1901 census] and although his job title isn’t known, he was most likely employed as a footman, with his duties clearly defined. He would have been a subordinate to the butler and if there was more than one footman, could have been placed in a ranking system according to height, size and good looks. Most were over six-feet tall, but additional inches could add additional income.

Often footmen were matched in size to maintain conformity in their joint appearance, and they were trained to act in unison. Frederick would have had a great many duties, ranging from seeing the head of the household and guests into their carriages on departure and receiving them on their arrival; polishing the household copper and plate; waiting at the table; and cleaning knives, cutlery, shoes and boots. Other duties at various times included trimming lamps; running errands; carrying coal; lighting the house at dusk; cleaning silver and gold; answering the drawing room and parlour bells; announcing visitors; waiting at dinner; attending the gentlemen in the smoking room following dinner; and attending in the front hall as guests were leaving. His uniform would have been white tie and tails with brass buttons that were most likely stamped with the Morgan family crest.

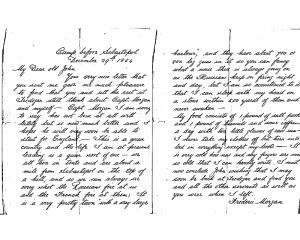

In 1891, the same time as our man from the Black Country was employed at Tredegar House, one of the servants wrote a letter to a friend, who was also a servant at a house in North Wales. Extracts from the letter give an indication of what the daily routine below stairs was like, particularly in the kitchen …

“There is a man in the kitchen who prepares and cooks all the meat, he’s the butcher. Then there is a man in the scullery, also a woman kept for washing up, and two still-room maids, and a woman comes every day to bake the bread. So there are five in the kitchen and two regularly in the scullery. I am afraid Miss Brown that sounds very much like a fairy tale, but when I tell you there are fourteen cold meats sent up every day for my Lord’s luncheon including four or five hot dishes, you will understand there is some work to be done in the kitchen alone. ”

For his service to Lord Tredegar, Frederick would have been paid £20 – £40 per annum, worked virtually every day from early morning till late at night, and only enjoyed some leisure time on a Sunday afternoon, or an occasional half day which was a reward if his work was deemed satisfactory and his behaviour conducted without blemish. Christmas at Tredegar House for Frederick would have been busier than ever. But come Twelfth Night he and the other servants would have been able to let their hair down and enjoy dancing and general merriment in the servants’ hall until the early hours. But woe-betide any who had too much to drink, for their duties started again at 6am the same morning.

Users Today : 15

Users Today : 15 Users Yesterday : 24

Users Yesterday : 24 Total Users : 75287

Total Users : 75287 Views Today : 69

Views Today : 69 Total views : 469663

Total views : 469663 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1